- Home

- Tuomas Kyrö

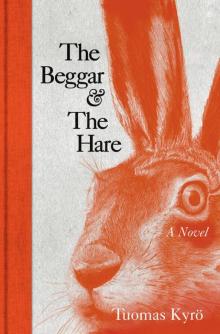

The Beggar and the Hare Page 19

The Beggar and the Hare Read online

Page 19

Martti.

You will also be able to recognise our house because the lights will be on. The other houses are empty. If I remember rightly the Hillanens were the last to move, that summer when there were an awful lot of mosquitoes.

Greetings,

Ulla and Pentti

P.S. The key will be under the flowerpot if we’re not at home. Make yourself coffee, there is always some in the box marked Co-op. But why would we leave our own house? My knees can’t manage the hills going down, and Ulla’s can’t manage them going up.

Vatanescu had that letter with him when one day in August he opened the Lahti agricultural show. He ate grilled sausages with his son, drank coffee in a disposable cup and listened to the voice of the people. There was a lot of it, that voice, and it varied both in volume and in content. Vatanescu had learned how to hold his cup lightly so that his fingers didn’t get scalded, and the deposits of mustard and ketchup on the hotdog wrapping paper no longer made him shudder. Simo Pahvi had taught him the importance of mastering gestures, posture and a convincing laugh. Even though pretending, he had to give an impression of deep and real sincerity. Most important of all, he had had to master the language, so that there would no longer be any distance between him and the natives. And after several months of language courses both intensive and hypnotic, he now understood and spoke Finnish surprisingly well.

He threw away the disposable cup, sucked the inside of the sausage and ate the skin as well. He shook hands with various interest groups and let them take photographs of him and Miklos. At the exhibitors’ request, they went to look at a Karelian herd bull and a drivable lawnmower from Minnesota, and the local football club presented Miklos with a jersey that had the number ten and the name Litmanen on the back. Another cup of coffee with a talkative local councillor, and then father and son returned to the back seat of the Million Merc.

Anneli Vatanescu-Pommakka was placed in her safety seat in the front of the car, and the rabbit crouched in a corner in the back.

‘Shall I take the long way home?’ Esko Sirpale asked.

Yes. The gravel and the potholes remind me of my childhood.

‘Perfect. But I’ll have a little music. These songs remind me of my youth.’

Vatanescu had tried to understand the words, tried to catch the mood, but the sound of this land was so melancholy that it did not open up to him. Except for a few foreign songs like ‘Genghis Khan’ whose singer, Frederik, had performed at Vatanescu’s victory concert on Helsinki’s Tapulikaupunki Square. And as Frederik now sang ‘Ramaya’, Vatanescu stretched forward to the front seat to tickle his daughter under her chin. Then he tickled the rabbit’s neck. Both daughter and rabbit sneezed. Esko Sirpale wound down the front windows, and Vatanescu the rear ones.

Vatanescu looked at the countryside with its fields, its wooden churches, its cowsheds, cemeteries, shopping centres with towers that reached to the sky, its service stations, moped riders, girls with bare midriffs, boys in baggy trousers, all the things that had been totally strange to him but now were forever familiar.

They arrived at yet another village, no different from the rest except for its name and the height of its church tower. Sirpale let the car roll past the cemetery; a squirrel climbed up the trunk of a spruce tree, jumping from branch to branch.

‘If you want to see Sports Roundup at home we’d better go back by the motorway.’

We have a more important matter to attend to now, one that affects a whole life.

Miklos can enter the address on the satnav.

597 Forest Close.

The paint was peeling, but the house stood at the top of the hill, straight as an oak. It had been built with modest means, as well as possible, with self-felled timber, on gravelly soil. Reason and moderation, dream and reality. There was a small potato patch, with currant bushes at regular intervals. At the bottom of the garden was a woodshed, with two neat stacks of firewood. There was a garden hose, a lawnmower, an axe, a saw and a chainsaw.

‘What are we going to do here?’ Miklos asked his father.

The owner knows the value of things. It doesn’t depend on their age.

It’s their usefulness and their sentimental value.

No one wants to lose what’s valuable.

Whoever built that shed is afraid of losing it. So he protects it and treasures it.

On the porch sat an elderly couple with grey hair and wrinkled faces, the man in a short-sleeved shirt and the woman in a summer dress. The woman’s head rested on her husband’s shoulder and they loved each other with the same tenderness they had shown on the Stockholm ferry. The depth of their feelings was confirmed by how the sight moved Vatanescu and startled Miklos. When Pentti saw the guests, he got up with difficulty and extended his hand.

‘We’ve been waiting for you every day.’ he said. ‘Good boots for a good boy.’

‘Eh?’ said Miklos.

Ulla fetched her better, gold-rimmed cups from the dresser and served coffee for Vatanescu. For Miklos there was a mug, fruit squash and a parcel wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. Vatanescu looked at the couple and then at his son, who was silently eating a large hunk of coffee bread. He followed it with a second hunk, and a third. He examined the football boots, he breathed in the smell of real leather, felt the tips of the toes. The boots were heavy, came from a different time, creaked. Never in a million years would he wear them; they would ruin his reputation and his athletic ability, but he had been brought up by his grandmother and he knew the right words to use so as not to offend the old couple.

‘They’re really valuable,’ he said. ‘They’d probably fetch hundreds of euros on an auction website.’

Ulla took Pentti’s hand and stroked it, then passed her hand over his rough cheek for a moment.

‘And the rabbit, we really adore it,’ Ulla said. ‘Do you have it with you?’

While Ulla inquired after the rabbit, Esko Sirpale removed the safety seat from the front of the car, got out and brought a tearful Anneli to Vatanescu. The rabbit also tried to escape through the open door, but it was shut in front of its nose. Long gone were the days of its freedom, the open road, its indispensable role in surprising turns of events. Now it had become either an extension of Vatanescu or a soft toy enclosed by four walls, without having sought either role. It bounced from the gearstick onto the back seat and then up to the rear window ledge.

From there it watched the humans recede, and heard the unpleasant sound of crying grow fainter. If it could, the rabbit would have covered its ears with its paws in order not to hear that noise. Human offspring were a strange force of nature engaged either in defecating, vomiting or smiling, the last of which the rabbit knew to be only a sign of wind anyway, and yet in those who looked after them they awoke enormous feelings of love and a desire to protect. These feelings in turn became houses, cars, insurance policies, summer cottages, holiday villages, playgrounds, educational institutions and amusement parks. The rabbit did not understand why human infants cried, for animals didn’t cry; they learned to cope as soon as they were able to walk. They couldn’t afford to cry, as there was always a fox or a hunter or a hawk about somewhere.

But this wasn’t really crying. Rather, it was a request and a demand.

Anneli was saying she was hungry, and she shook her little fist in the air to emphasise the fact.

Ulla got up from her chair to look at the child, and quietly sang to her. The grandfather clock ticked from the wall. The refrigerator gave a rattling snore now and then – as did Pentti – and Ulla touched the tip of Anneli Vatanescu-Pommakka’s nose, whereupon the little girl’s crying stopped for a moment. Vatanescu took the child out of the baby seat and calmed her, then fished a bottle with a teat and a carton of baby milk out of his briefcase. With the ease of an expert he unscrewed the teat, opened the carton with his teeth and poured the correct amount into the bottle.

Drink your milk, little one who was conceived on the train.

They would have

made good parents. They have a house that was made for it, a solid post-war veterans’ house. Flexible interiors, an unused room upstairs.

A wide, well-tended stretch of forest, with clear boundaries. A reasonable number of wild nocturnal carnivores.

There’s a carrot patch and a potato patch.

All they need now is a child, who would be happy living there.

They will still make good parents.

Drink your milk, little one.

The window on the driver’s side was partly open. The rabbit, forgotten and thirsty, wriggled its way out and wondered if it should leap away across the fields into the wilds or out onto the road to dash about in desperation this way and that, as others of its species had done as their last deed. The rabbit saw Vatanescu inside the house with the baby on his knee. The rabbit saw Miklos helping himself to a fourth hunk of coffee bread. The rabbit studied Pentti and Ulla, Ulla and Pentti, and through the porch flowed something powerful, something that only an animal could sense without a word being exchanged. The rabbit looked at the little boy who had ignited into being within the old man when Miklos arrived, and the surge of protective care in the old woman when the little baby was also present. The rabbit quietly hopped towards the gently crumbling concrete steps of the veterans’ house, put its paws on the first step, then on the second, pushed its small head through the doorway and slipped inside. It bounded over the rag rug, traversed the tip of Esko Sirpale’s foot and jumped up on the bench. From there it leapt onto the table, circumnavigating a pack of butter, a carton of whole milk and a tin of anchovies, and arrived in front of Ulla and Pentti. The rabbit threw itself onto Ulla’s lap. The rabbit turned its gaze on Pentti, the rabbit turned its gaze on Ulla, the rabbit smelled the smells of this home, the smell of flannel, of sweat, of resin, of tar, of yeast bread and pine soap. The rabbit made itself into a warm, homely bundle. The rabbit instantly made itself irreplaceable, Ulla and Pentti’s very own Violet or Martti.

Good rabbits circulate, we might think, as Ulla and Pentti make a nest for the rabbit in a cardboard box. Lousy Mercs roll, we might think, as Esko Sirpale steers the car along the forest road towards the highways, towards the rest of the life that is beginning on this day.

Esko Sirpale puts a cassette in the car stereo; it is one of Tapio Rautavaara’s best songs, and even Vatanescu knows the tune and the words, because this song about the Sandman is the one that is certain to make Anneli Vatanescu-Pommakka fall asleep, and Vatanescu himself, and all of his numerous family, and the whole of Finland too, because it’s a good song to fall asleep to.

…and he has a car that is blue

and that car hums along unseen

whirs and whirs as it carries you

to the blue land of the dream…

Copyright

First published in English in 2014 by Short Books

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

This ebook edition first published in 2014

Original title “Kerjäläinen ja jänis”

First published in Finnish by Siltala Publishing in 2011, Helsinki, Finland Published by arrangement with Werner Söderström Ltd. (WSOY)

All rights reserved

© Tuomas Kyrö 2011

The right of Tuomas Kyrö to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

English language translation copyright © David McDuff 2014

ISBN 978–1–78072–165–1

Cover design by Two Associates

Cover illustration by Mike Hughes

The Beggar and the Hare

The Beggar and the Hare